When Faith Harms: Understanding Religious Trauma in the Family

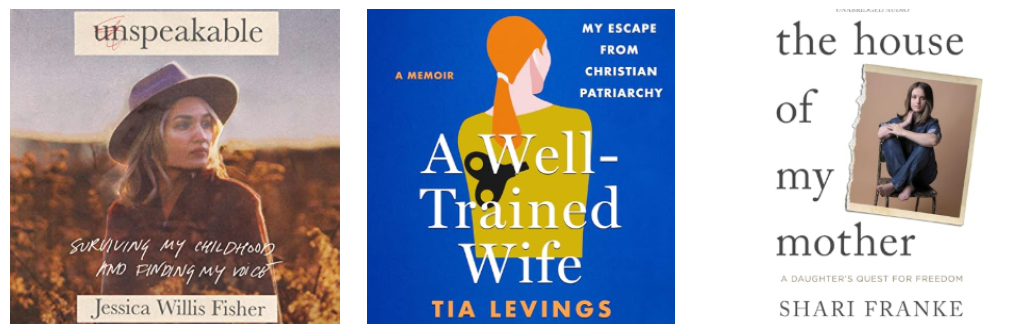

An image with the cover of three books: Unspeakable, A Well Trained Wife, and The House of my Mother

Religious trauma is often sustained not by ignorance alone, but by systems that prioritise authority and certainty over empathy and accountability. Even when intentions are framed as righteous, the impact on those subjected to these dynamics can be deeply damaging. Harm is not diminished because it occurs within a faith context, nor because it is justified through spiritual language.

What Three Books Tell Us About Religious Trauma in Families

This becomes especially clear when we examine the lived experiences described in A Well-Trained Wife by Tia Levings, The House of My Mother by Shari Franke, and Unspeakable by *Jessica Willis Fisher. Each memoir offers a different lens on how religious trauma can take root within family systems — not primarily through overt cruelty, but through control, fear, and the misuse of spiritual authority.

In A Well-Trained Wife, Tia Levings describes a marriage shaped by rigid religious expectations around submission, obedience, and prescribed gender roles. What becomes evident is how theology can be used to normalise imbalance and silence dissent. The expectation to be a “godly wife” gradually eclipses personal agency, emotional safety, and even basic self-trust. Religious language is used to sanctify control — framing endurance as faithfulness and suffering as spiritual growth. Within this system, questioning is not merely discouraged; it is reframed as moral failure.

Levings’ account makes clear that these dynamics do not remain abstract or theoretical. The environment she describes involves escalating coercive control, increasing isolation from family and support networks, and the use of a homeschooling lifestyle that further limited outside influence or intervention. Over time, this isolation deepened, and the erosion of autonomy became profound. What began as religious expectation gradually escalated into physical abuse that placed both her and her children in danger. Her eventual need to flee for safety underscores a sobering reality: when spiritual control goes unchecked, it can create the conditions in which physical harm becomes possible. What begins as doctrine can ultimately become entrapment. This is an example of how religious ideologies can perpetuate dynamics associated with coercive control and domestic violence.

The House of My Mother offers a different but equally confronting perspective. Shari Franke’s memoir reveals how religious trauma can develop within a family system led by a controlling parent — in this case, a mother — whose authority is reinforced through moral certainty, rigid discipline, and a carefully curated public image. The book challenges the assumption that religious control is always male-driven, demonstrating instead how power can operate through anyone granted unquestioned authority.

Within this environment, children learn early that love is conditional, obedience is safety, and emotional expression is dangerous. Franke describes severe emotional and physical abuse of her younger siblings, abuse that was hidden behind religious language, social respectability, and online performance. Her mother’s eventual imprisonment highlights the seriousness of the harm involved. The memoir also reveals how children raised in such systems are often left vulnerable to further exploitation, including Shari’s own experience of sexual abuse by an older man in her church. The overlap between spiritual control, silence, and exposure to further abuse is not incidental — it is systemic.

Jessica Willis Fisher’s Unspeakable further exposes how secrecy, rigid male authority, and protection of reputation can become central organising forces within religious families. Her story reveals how loyalty to faith, ministry, and public image repeatedly took precedence over the safety of children. Her father’s sexual abuse of multiple family members was minimised or ignored for years, illustrating how deeply denial can take root when acknowledging harm threatens the stability of a religious system.

In such environments, silence becomes a survival strategy. Speaking up risks disbelief, spiritual condemnation, or complete social exile. Children learn quickly that truth is dangerous and that preserving the family or ministry matters more than their own wellbeing. Over time, this teaches them to carry suffering alone.

Across all three memoirs, a consistent pattern emerges: religious trauma within families is rarely about isolated acts of cruelty. It is about systems that reward compliance, discourage questioning, and equate authority with righteousness. Children raised in these environments do not have the capacity to challenge what they are taught. Instead, they adapt in order to survive — often at significant psychological cost.

These stories do not illustrate that faith itself is the problem. Rather, they reveal what happens when faith becomes entangled with fear, control, and unexamined power. They invite a deeper reckoning with how religious communities can better protect the vulnerable, value truth over image, and create spaces where safety, dignity, and compassion are truly upheld.

If you are seeking support, Refuge Psychology offers compassionate, evidence-based care for those recovering from abuse and complex trauma—including those harmed in religious or institutional contexts. Together, we can work toward healing that restores your sense of safety, dignity, and hope. You can contact me to find out more information.

You can learn more or book a confidential appointment:

References

Levings, T. (2024). A well-trained wife: My escape from Christian patriarchy. Tyndale House Publishers.

Franke, S. (2024). The house of my mother: A daughter’s quest for freedom. Gallery Books.

Willis Fisher, J. (2022). Unspeakable: Surviving my childhood and finding my voice. Worthy Publishing.

Disclaimer

Any stories or examples provided are illustrative only and do not describe a specific client, person, or event. Some of the information presented relates to health and mental health issues but is not intended as medical advice. It is offered for general informational purposes. While every effort is made to ensure accuracy, some information may reflect opinion or emerging research. Your personal circumstances have not been considered, so any reliance on this material is at your own risk. Please seek independent professional advice before acting on any of it. Find the full terms of service here: Terms of Service | Refuge Psychology